Philip K Dick: the writer who witnessed the future

Science Fiction is a genre that I felt I was well suited for when I started writing. I am a scientist by training, a physicist in particular, and thereby it would be easy to create new worlds and new theories to explore and develop. Yet I found this genre to be most difficult to write. Prolific science fiction writers have a vision of the future and develop new technologies and theories that decades later tend to become our reality. One such writer is Isaac Asimov, of course, Arthur C. Clarke, and Phillip K. Dick. In my effort to address this genre I wrote two short stories called “We the People of Earth” and Patient Zero. Both had footing in our current reality but posed the question of where we are going as a society and as a world. The following article written by Adan Scovell reviews the works of Phillip K. Dick. My favorite is “The Man in the High Castle”.

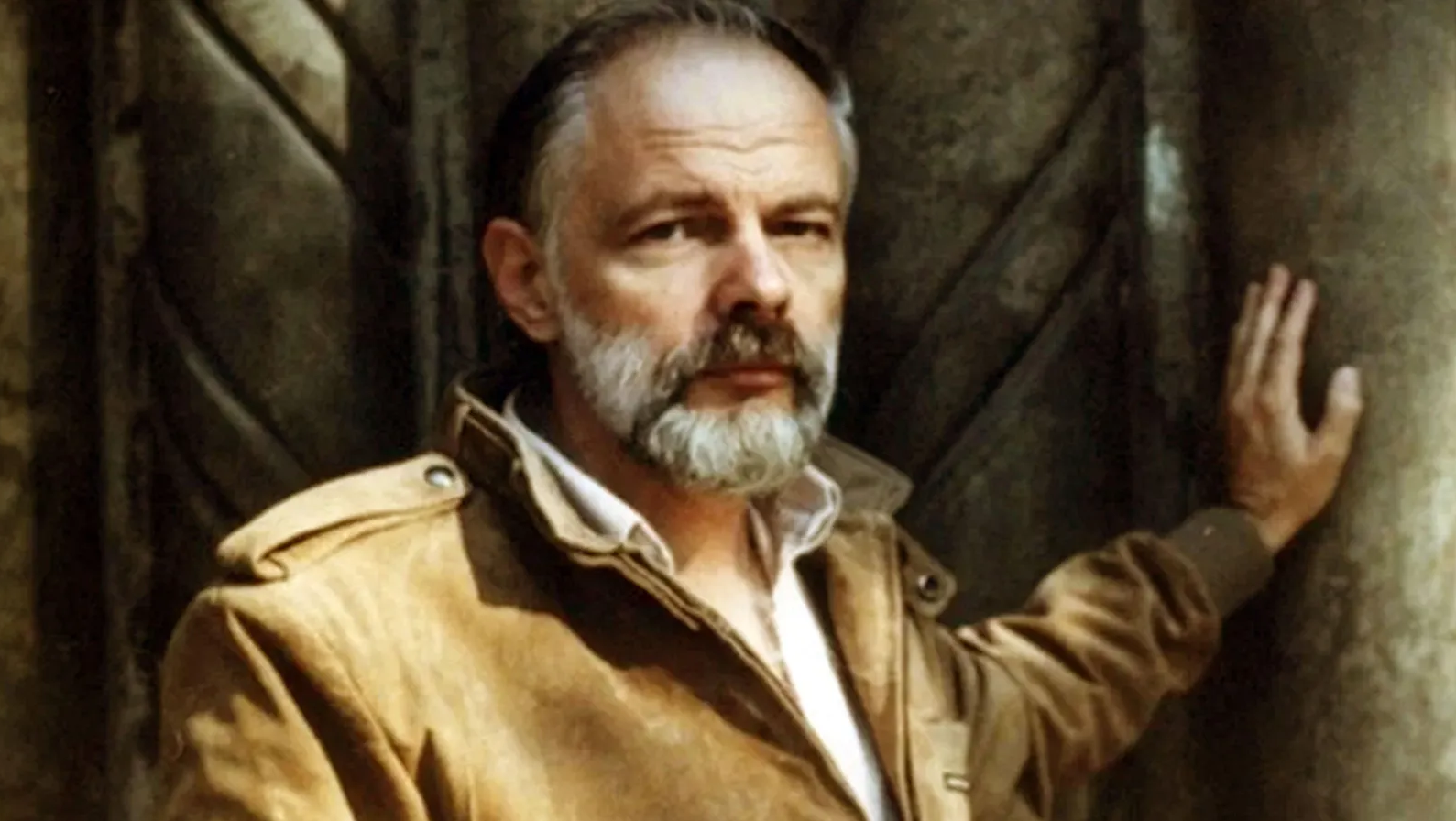

Forty years since the death of the sci-fi author – whose stories have inspired films like Blade Runner and Minority Report – Adam Scovell explores how prophetic his work has been.

“I am in passport control. I can see my face on a screen. The technology recognizes me and lets me through. I scan codes showing my vaccination status and recent Covid test results. The machines assess the data regarding my health and microbiology. Through into the waiting room, people are staring into little screens. A strangely large number have the camera flipped, and are capturing their faces at different angles, as if they’ve forgotten what they look like. I open my laptop and join in. I give my details to a company to enter the digital realm. Adverts tailored to my personality pop up. They know me better than I know myself.”

This is 2022. And 2022 is a Philip K Dick novel.

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20220301-philip-k-dick-the-writer-who-witnessed-thefuture.

“Writers of science fiction often feel more prescient than others. Whether it’s the threat to women’s rights in the work of Margaret Atwood, the architectural and social dystopias of JG Ballard’s novels, or the internet-predicting world of E M Forster’s The Machine Stops (1909), the genre is replete with prophetic writers dealing with ever more familiar issues.

Out of all such writers, few seem a more unlikely seer of our times than the US author Philip K Dick, who died 40 years ago today at the age of 53. In a remarkably prolific 30-year period of work, Dick authored 44 novels and countless short stories, adaptations of which went on to redefine science fiction on screen – in particular Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), which was based on Dick’s story Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and Paul Verhoeven’s Total Recall (1990), which took his 1966 short story We Can Remember It for You Wholesale as its source material. More recently Dick’s novel The Man in the High Castle (1962) has been turned into a hit Amazon series.

The man behind the visionary worlds

Dick was not simply an effective writer of strange fictions, but an unusual person in his own right. Burdened by deteriorating mental health, visions, and what he alleged were all manner of paranormal experiences – many of which were woven into his expansive oeuvre – Dick had a troubled and fragmented relationship with reality. In the 1970s, the author began to experience two parallel timelines of his own life, his thoughts invaded in 1974 by what he told interviewer Charles Platt was a “transcendentally rational mind”, something he had many names for, but chiefly VALIS; an acronym for Vast Active Living Intelligence System. It became the subject of one of his late semi-autobiographical works, the 1981 novel VALIS, published not long before his death.

Whether his visions were medical or supernatural, one thing is clear: Dick had a startling ability to foreshadow the modern world. Celebrated science-fiction and fantasy author Stan Nicholls suggests Dick’s work is prescient because it explored the future through the then-present. “His stories posited the ubiquitousness of the internet, virtual reality, facial recognition software, driverless cars and 3D printing,” Stan Nicholls tells BBC Culture – while also pointing out that “it’s a misconception that prediction is the primary purpose of science fiction; the genre’s hit rate is actually not very good in that respect. Like all the best science fiction, his stories weren’t really about the future, they were about the here and now.” Indeed, Dick’s incorporation of everyday aspects of post-War America into his futures has meant that his worlds possessed a surreal familiarity.

Nevertheless, the way he also anticipated particular technological and societal developments remains striking. “He had a lot of scientific images of the way the future would work,” says

Anthony Peake, author of the biography A Life of Philip K Dick: The Man Who Remembered the Future (2013). “For instance, he had a concept that you would be able to communicate advertising to people directly, that you’d be able to know them so well that you could target the marketing precisely to their anticipations. And this is exactly what is happening online.”

Peake could be referring to any number of Dick’s stories, the most famous in this regard being the 1956 story The Minority Report, adapted for the cinema in 2002 by Steven Spielberg. Screen adaptations have often latched on to the invasive nature of advertising in his work, yet the writer explored the theme in far more detail than as merely a background aesthetic (which is how it manifests on screen).

In the 1954 short story Sales Pitch, for example, the idea of aggressive yet unnervingly personalized advertising finds fruition in a demented machine that constantly markets itself at the story’s protagonist. In the 1964 novel The Simulacra, on the other hand, advertising is embodied by a mechanical fly-like creature. As he writes in the novel, the “commercial, fly-sized, began to buzz out its message as soon as it managed to force entry. ‘Say! Haven’t you sometimes said to yourself, I’ll bet other people in restaurants can see me!'”. It’s a physical equivalent of spam or tailored adverts popping up on social media.

Dick’s political ideas

Dick’s work often had a political dimension, too. The Man in the High Castle, for example, imagines an alternative history in which the Nazis won World War Two. In lesser-known works such as Eye in the Sky (1957), this politics is more of its period. In the novel, a group of people become stuck in various different worlds conjured by each individual, thanks to a malfunctioning particle accelerator. The narrative focuses especially on a world dreamed up by a communist member of the group who has been dismissed from the laboratory for holding such beliefs. The twist is that the world conjured with obvious over-the-top Marxist leanings is, in fact, the product of the lab security chief who is also a communist but in secret. The book showed that Dick’s politics could not be simplified into a straightforward description of left or right, as he was biting in his attacks on both the McCarthy-esque witch hunts of the period as well as the more evangelical leanings of communism.

Dick was altogether anti-establishment: his stories feature authorities and companies consistently abusing their power, especially when it comes to surveillance. His worlds are ultra-commodified, and their citizens addicted to materialism, while celebrity, media, and politics meld to create nightmarish, authoritarian scenarios, usually topped off with a heavy dose of technocracy and bureaucracy.

This bureaucracy manifested itself in various forms throughout his work. In his 1974 novel Flow My Tears, the Policeman Said, set in a dystopian 1988 where the US is again ruled by a dictatorship, a singer and TV host called Jason Taverner wakes up to find himself in a world in which he is suddenly no longer famous and lacks the many documents now required to avoid being arrested and sent to a labor camp.

Taverner may struggle to get beyond the basic spot checks and cordons in Flow My Tears, but other Dick characters struggle to do the most basic things, even in their own homes. In the 1969 novel Ubik, a character ends up arguing with the door to his apartment, as he doesn’t have the change to get in via its coin-operated mechanism. The door even threatens to sue him when he tries to break it down. Every aspect of the lived experience becomes commodified in Dick’s work, an aspect that feels deeply poignant. Dick sees a paywall future, where the amenities of our own homes all require a token offering, even if today that offering is personal information rather than loose change.

Putting aside Dick’s ability to foreshadow the future we now take for granted, his most unnerving vision was of the world itself ultimately being a simulation. Dick’s reality was already a fragile and complex one. In many of his later books, the idea of reality being a façade grew as a dominant theme. “Dick argued we were existing in a simulation,” Peake suggests. “Elon Musk caused controversy quite recently by effectively venturing the same idea.”

Whether his visions were, as he believed, a product of glitches in the simulation or his fading mental health, one thing is for certain: the world in which the work of Philip K Dick is celebrated today feels ever closer to the ones imagined by this most unique and exceptional of writers.”