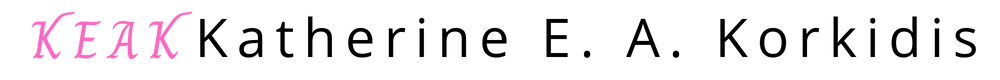

The Multiverse of Everything Everywhere All at Once, the 2023 Oscar winner for Best Picture.

Movies can’t get enough of exploring these questions. From Oscar winners like Everything

Everywhere All at Once, to superhero blockbusters like Dr. Strange in the Multiverse of Madness, science fiction stories are full of creative interactions between alternate realities.

And depending on which cosmologist you ask, the concept of a multiverse is more than pure fantasy or a handy storytelling device.

It brings up the questions of –

What lies beyond the edges of the observable universe?

Is it possible that our universe is just one of many in a much larger multiverse?

The article published in National Geographic entitled What is the multiverse—and is there any evidence it really exists?

Written By Nadia Drake addresses these questions below.

Published March 13, 2023

What lies beyond the edges of the observable universe? Is it possible that our universe is just one of many in a much larger multiverse?

Movies can’t get enough of exploring these questions. From Oscar winners like Everything Everywhere All at Once to superhero blockbusters like Dr. Strange in the Multiverse of Madness, science fiction stories are full of creative interactions between alternate realities. And depending on which cosmologist you ask, the concept of a multiverse is more than pure fantasy or a handy storytelling device.

Humanity’s ideas about alternate realities are ancient and varied—in 1848 Edgar Allan Poe even wrote a prose poem in which he fancied the existence of “a limitless succession of Universes.” But the multiverse concept really took off when modern scientific theories attempting to explain the properties of our universe predicted the existence of other universes where events take place outside our reality.

“Our understanding of reality is not complete, by far,” says Stanford University physicist Andrei Linde. “Reality exists independently of us.”

If they exist, those universes are separated from ours, unreachable and undetectable by any direct measurement (at least so far). And that makes some experts question whether the search for a multiverse can ever be truly scientific.

Will scientists ever know whether our universe is the only one? We break down the different theories about a possible multiverse—including other universes with their own laws of physics— and whether many versions of you could exist out there.

What is a multiverse?

The multiverse is a term that scientists use to describe the idea that beyond the observable universe, other universes may exist as well. Multiverses are predicted by several scientific theories that describe different possible scenarios—from regions of space in different planes than our universe, to separate bubble universes that are constantly springing into existence.

The one thing all these theories have in common is that they suggest the space and time we can observe is not the only reality.

Okay … but why do scientists think there could be more than one universe?

“We cannot explain all the features of our universe if there’s only one of them,” says science journalist Tom Siegfried, whose book The Number of the Heavens investigates how conceptions of the multiverse have evolved over millennia.

“Why are the fundamental constants of nature what they are?” Siegfried wonders. “Why is there enough time in our universe to make stars and planets? Why do stars shine the way they do, with just the right amount of energy? All of those things are questions we don’t have answers for in our physical theories.”

Siegfried says two possible explanations exist: First, that we need newer, better theories to explain the properties of our universe. Or, he says, it’s possible that “we’re just one of many universes that are different, and we live in the one that’s nice and comfortable.”

What are some of the more popular multiverse theories?

Perhaps the most scientifically accepted idea comes from what’s known as inflationary cosmology, which is the idea that in the minuscule moments after the big bang, the universe rapidly and exponentially expanded. Cosmic inflation explains a lot of the observed properties of the universe, such as its structure and the distribution of galaxies.

“This theory at first looked like a piece of science fiction, although a very imaginative one,” says Linde, one of the architects of cosmic inflationary theory. “But it explained so many interesting features of our world that people started taking it seriously.”

One of the theory’s predictions is that inflation could happen over and over again, perhaps infinitely, creating a constellation of bubble universes. Not all of those bubbles will have the same properties as our own—they might be spaces where physics behaves differently. Some of them might be similar to our universe, but they all exist beyond the realm we can directly observe.

What are some other ideas?

Another compelling type of multiverse is called the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, which is the theory that mathematically describes how matter behaves. Proposed by physicist Hugh Everett in 1957, the many-worlds interpretation predicts the presence of branching timelines, or alternate realities in which our decisions play out differently, sometimes producing wildly different outcomes.

“Hugh Everett says, Look, there’s actually an infinite number of parallel Earths, and when you do an experiment and you get the probabilities, basically all that proves is that you live on the Earth where that was the outcome of that experiment,” says physicist James Kakalios of the University of Minnesota, who has written about the physics (or not) of superheroes. “But on other Earths, there’s a different outcome.”

According to this interpretation, versions of you could be off living the many different possible lives you could have led if you’d made different decisions. However, the only reality that’s perceptible to you is the one you inhabit.

So where do all of those other Earths exist?

They’re all overlapping in dimensions we can’t access. MIT’s Max Tegmark refers to this type of multiverse as a Level III multiverse, where multiple scenarios are playing out in branching realities.

“In the many-worlds interpretation, you still have an atomic bomb, you just don’t know exactly when it’s going to go off,” Linde says. And maybe in some of those realities, it won’t.

By contrast, the multiple universes predicted by some theories of cosmic inflation are what Tegmark calls a Level II multiverse, where fundamental physics can be different across the different universes. In an inflationary multiverse, Linde says, “you do not even know if, in some parts of the universe, atomic bombs are even possible in principle.”

So if I want to meet myself, how do I get there? Can we travel between multiverses?

Unfortunately, no. Scientists don’t think it’s possible to travel between universes, at least not yet.

“Unless a whole lot of physics we know that’s pretty solidly established is wrong, you can’t travel to these multiverses,” Siegfried says. “But who knows? A thousand years from now, I’m not saying somebody can’t figure out something that you would never have imagined.” Is there any direct evidence suggesting multiverses exist?

Even though certain features of the universe seem to require the existence of a multiverse, nothing has been directly observed that suggests it actually exists. So far, the evidence supporting the idea of a multiverse is purely theoretical, and in some cases, philosophical.

Some experts argue that it may be a grand cosmic coincidence that the big bang forged a perfectly balanced universe that is just right for our existence. Other scientists think it is more likely that any number of physical universes exist, and that we simply inhabit the one that has the right characteristics for our survival.

An infinite number of alternate little pocket universes, or bubbles universes, some of which have different physics or different fundamental constants, is an attractive idea, Kakalios says. “That’s why some people take these ideas kind of seriously, because it helps address certain philosophical issues,” he says.

Scientists argue about whether the multiverse is even an empirically testable theory; some would say no, given that by definition a multiverse is independent from our own universe and impossible to access. But perhaps we just haven’t figured out the right test.

Will we ever know if our universe is just one of many?

We might not. But multiverses are among the predictions of various theories that can be tested in other ways, and if those theories pass all of their tests, then maybe the multiverse holds up as well. Or perhaps some new discovery will help scientists figure out if there really is something beyond our observable universe.

“The universe is not constrained by what some blobs of protoplasm on a tiny little planet can figure out, or test,” Siegfried says. “We can say, This is not testable, therefore it can’t be real— but that just means we don’t know how to test it. And maybe someday we’ll figure out how to test it, and maybe we won’t. But the universe can do whatever it wants.”

This article originally published on May 4, 2022.