`Dostoyevsky, Just After His Death Sentence Was Repealed, on the Meaning of Life

The first time I read Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky I was a young impressionable teen. His works made me question my understanding of my faith and life, particularly Crime and Punishment from its first sentence to its conclusion. As I read this Dostoevsky novel, I felt myself asking, “What does it all mean?” The stories refuse to allow me to passively sit back and enjoy the ride. Instead, this novel probed me. Am I a good person? Who is God and what role does he play in my life? Was God incarnated? Is there resurrection? How do I plan to confront my mortality? Deep questions, probing questions that time would indeed answer for me and for Dostoyevsky.

The book was originally conceived as a long short story or possibly a novella to be written in the first person, and extensive fragments of a possible original work can be found. These fragments are in the form of Raskolnikov’s confession, which was intended to recount the murder retrospectively after the process of repentance had already done its work. Dostoevsky abandoned his original idea in favor of the complex drama of inner self-discovery that finally emerged as his first great masterpiece. This process of self-discovery was there from the very start in the letter outlining the first idea for the book, Dostoevsky writes that, after the murder, “unresolved questions arise before the murderer, unsuspected and unexpected feelings torment his heart.” But this idea blossomed out into Raskolnikov’s dialectic of inner evolution only when Dostoevsky abandoned the first-person form for the dramatic novel. The confession could only have begun after all the “unsuspected and unexpected feelings” had done their work; and so it would have been impossible to show them in action on Raskolnikov with the requisite force and unexpectedness.

The same letter also provides us with valuable information about the ideological genesis of the book. Dostoevsky describes the central figure as “a young man expelled from the university, a petty bourgeois by background, living in the most extreme poverty,” who has “become obsessed with badly thought out ideas which happen to be in the air” and who decides to kill a useless old moneylender for the benefit of his family and, ultimately, of humanity. From this period of Russian politics, it is clear that Dostoevsky can only be referring to the Utilitarian egoism which then formed the ethical basis of Russian radicalism and almost let to his execution. He was born into czarist Russia and exposed in his 20s to Marxism. He was arrested as a radical and setup for a mock execution. Although he remained in exile after his release, Dostoevsky wrote several novels as a nomad, including Crime and Punishment, The Idiot, and Demons. He returned to Russia in 1871 and wrote the greatest novel of all time, The Brothers Karamazov.

Only by the time that Dostoevsky writes The Brothers Karamazov does he show fully the hope found in the charity of God. The novel is a mystery story, but with metaphysical import. The Brothers Karamazov challenges readers’ assumptions that we are autonomous individuals who may fashion our lives into whatever we desire them to be. Instead, you witness three brothers — Dmitri, Ivan and Alyosha Karamazov — who, because of their despicable and negligent father, have had to make their own way in the world. Yet each has had to come to terms with their father’s influence on who they are, have sought to choose better father figures to emulate and, ultimately, learn they must die to themselves to become who they are meant to be.

“To be a human being among people and to remain one forever, no matter in what circumstances, not to grow despondent and not to lose heart—that’s what life is all about, that’s its task.”

The following commentary giving us more insight on this author is written by Maria Popova.

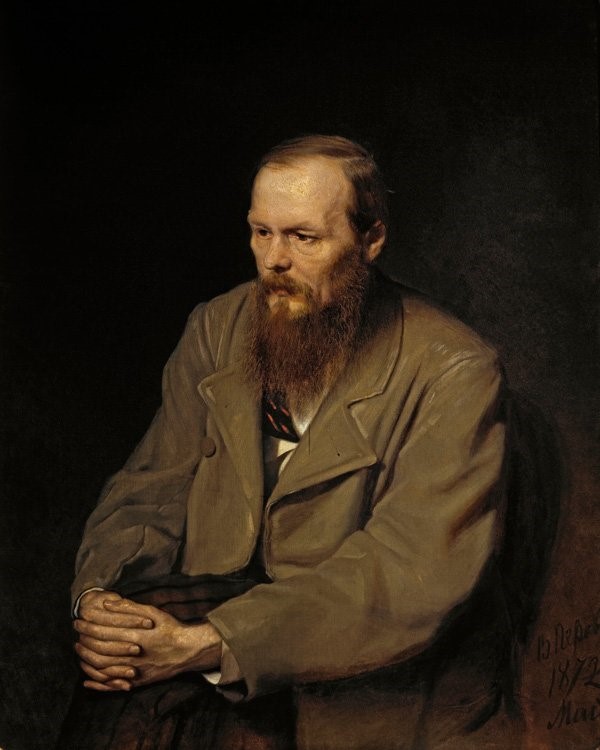

“I mean to work tremendously hard,” the young Fyodor Dostoyevsky (November 11, 1821–February 9, 1881) resolved in contemplating his literary future, beseeching his impoverished mother to buy him books. At the age of twenty-seven, he was arrested for belonging to a literary society that circulated books deemed dangerous by the tsarist regime. He was sentenced to death. On December 22, 1849, he was taken to a public square in Saint Petersburg, alongside a handful of other inmates, where they were to be executed as a warning to the masses. They were read their death sentence, put into their execution attire of white shirts, and allowed to kiss the cross. Ritualistic sabers were broken over their heads. Three at a time, they were stood against the stakes where the execution was to be carried out. Dostoyevsky, the sixth in line, grew acutely aware that he had only moments to live.

And then, at the last minute, a pompous announcement was made that the tsar was pardoning their lives — the whole spectacle had been orchestrated as a cruel publicity stunt to depict the despot as a benevolent ruler. The real sentence was then read: Dostoyevsky was to spend four years in a Siberian labor camp, followed by several years of compulsory military service in the tsar’s armed forces, in exile. He would be nearly forty by the time he picked up the pen again to resume his literary ambitions. But now, in the raw moments following his close escape from death, he was elated with relief, reborn into a new cherishment of life.

He poured his exultation into a stunning letter to his brother Mikhail, penned hours after the staged execution and found in the first volume of the out-of-print collection of his complete correspondence, the 1988 treasure Dostoevsky Letters (public library).

A century before Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl offered his hard-won assurance that “everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances,” Dostoyevsky writes:

Brother! I’m not despondent and I haven’t lost heart. Life is everywhere, life is in us ourselves, not outside. There will be people by my side, and to be a human being among people and to remain one forever, no matter in what circumstances, not to grow despondent and not to lose heart — that’s what life is all about, that’s its task. I have come to recognize that. The idea has entered my flesh and blood… The head that created, lived the higher life of art, that recognized and grew accustomed to the higher demands of the spirit, that head has already been cut from my shoulders… But there remain in me a heart and the same flesh and blood that can also love, and suffer, and pity, and remember, and that’s life, too!

Still, even though this elation, the animating force of his being — his identity as a writer — grounds him into a depth of despair. “Can it be that I’ll never take pen in hand?” he asks in sullen anticipation of the next four years at the labor camp. “If I won’t be able to write, I’ll perish. Better fifteen years of imprisonment and a pen in hand!” But he quickly recovers his electric gratitude for the mere fact of being alive and, reassuring his brother not to grieve for him, continues: